Yaesu FTX-1 MARS Mod – Complete Guide and In-Depth Explanation

The Yaesu FTX-1 series has earned a strong reputation among radio enthusiasts as a compact, rugged, and highly capable handheld transceiver. In its standard configuration, the radio is intentionally limited to transmitting only within the authorized amateur radio bands. These restrictions aren’t shortcomings but deliberate design choices: they ensure that operators stay compliant with national regulations, avoid interfering with critical services, and maintain the legal framework that keeps the RF spectrum usable for everyone.

Still, it doesn’t take long for new owners to encounter discussions about the so-called MARS/CAP modification. This modification—well known in ham radio circles—removes the factory-imposed transmit limits and allows the radio to operate across a much wider frequency range. For some operators, it’s simply an interesting technical exercise that reveals what the hardware is truly capable of. For others, especially those involved in organized emergency communication programs, it provides the flexibility needed to support inter-agency channels outside the standard amateur allocations. And for a small but officially recognized group of licensed volunteers in MARS (Military Auxiliary Radio System) or CAP (Civil Air Patrol), expanded transmit capability is not an option at all—it’s a functional requirement.

But the existence of the MARS mod often leads to misunderstandings. Many hobbyists overestimate what the modification does, underestimate the legal implications, or assume it magically turns a ham radio into a wideband communication tool suitable for any situation. In reality, the procedure comes with important limitations, responsibilities, and potential consequences. Before anyone considers opening the radio, cutting diodes, or changing internal settings, it’s crucial to understand what the MARS/CAP mod is meant for, what it cannot do, and what risks are involved in making the modification.

The following guide provides a clear, detailed explanation of the MARS modification, including its purpose, scope, legal boundaries, practical use cases, and why responsibly trained operators approach it with caution rather than excitement.

UPDATE:

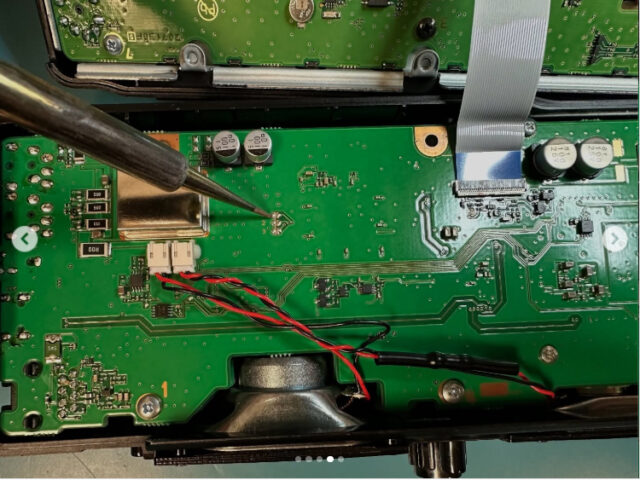

Although the so-called MARS/CAP modification for the Yaesu FTX-1 series is often described online as a “simple hardware hack”, it is still an invasive hardware procedure on a modern, densely packed PCB. Before you even think about opening the radio, you should:

-

make sure you are legally allowed to use an expanded-coverage transceiver,

-

accept that the procedure will almost certainly void the warranty,

-

and understand that a single slip with the soldering iron can irreversibly damage the radio.

With that in mind, here is the documented process for the FTX-1 series, presented in a more structured way and with added cautionary notes.

1. Power down and disconnect everything

-

Turn the radio off completely.

-

Remove all power sources: detach the battery pack and unplug any external DC power supply.

-

It’s good practice to press the PTT or a front panel key briefly after removing the power to discharge any remaining energy in the circuits.

Reason: working on a powered board risks short circuits, component damage and, in extreme cases, personal injury.

2. Remove the speaker/bottom cover

-

Place the radio face-down on a soft surface to avoid scratching the display.

-

On the bottom speaker cover, locate the three black screws.

-

Carefully unscrew them and set them aside in a small container so they don’t get lost.

-

Gently lift off the speaker/bottom cover. Don’t force anything – if it resists, double-check that all screws are really out.

3. Access the hidden screws under the cover

-

Under this cover you will find three additional silver screws securing the chassis.

-

Remove these hidden screws as well. Again, keep track of which screws came from where – mixing them up during reassembly can cause mechanical stress or improper fit.

4. Loosen the front unit

-

Turn the radio around and look at the back side.

-

At the top of the rear case, remove the three black screws that hold the front unit to the RF/logic unit.

-

Once these are out, the front and RF sections are no longer rigidly locked together.

5. Carefully separate the front and RF units

-

Starting from one side, gently separate the front panel assembly from the RF unit.

-

Take your time: there are flex cables and wiring between the sections. Do not pull or twist violently.

-

If a cable feels tight, stop and inspect the routing – the goal is to hinge the parts apart, not tear anything loose.

At this point you should be able to see the main PCB where the configuration jumpers are located.

6. Locate “Jumper 1” and enable MARS/CAP mode

-

On the mainboard, identify Jumper 1 (often labelled “JP1” or similar, depending on the revision).

-

According to the documented procedure, shorting this jumper activates the extended MARS/CAP transmit configuration.

-

Using a fine-tip soldering iron and suitable solder, create a clean, minimal solder bridge across the jumper pads.

Important safety notes:

-

Avoid using excessive solder. A large blob can flow onto nearby SMD components or traces.

-

Do not scratch or cut other areas of the PCB.

-

Ideally, use magnification (e.g. a headband loupe) to ensure the bridge connects only the intended pads, and nothing else.

7. Reassemble the radio

-

Once the solder joint has cooled and you have visually confirmed there are no unintended bridges, begin reassembly.

-

Reattach the front unit to the RF unit, making sure no cables are pinched or misaligned.

-

Replace the three black screws at the top of the rear side.

-

Reinstall the three silver screws under the bottom cover.

-

Finally, put the speaker/bottom cover back on and secure it with its three black screws.

Reassembly should never require force. If something doesn’t fit, back up a step and check alignment.

8. Perform a factory reset

-

Reinsert the battery (or connect external power), then power up the radio.

-

Follow the manufacturer’s documented factory reset procedure for the FTX-1 series.

-

This reset step is crucial: it forces the radio’s firmware to detect the new hardware configuration (the bridged jumper) and apply the appropriate MARS/CAP settings.

After the reset, the radio should boot with the expanded configuration active—assuming the modification was performed correctly and no hardware damage occurred.

Why “easy” is relative

On paper, this sequence looks straightforward: remove some screws, bridge one jumper, reassemble, reset. In reality, modern handheld transceivers use:

-

very small SMD components,

-

tight mechanical tolerances,

-

and delicate flex connections.

A momentary slip can:

-

rip a flex cable,

-

lift a pad from the PCB,

-

or create a nearly invisible solder bridge that causes intermittent faults.

That’s why experienced radio amateurs often warn newcomers: what seems like a “simple MARS mod” in a forum post is only simple if you have the right tools, a steady hand, and prior practice on scrap boards. Before modifying any FTX-1 in real life, it’s worth asking yourself whether:

-

you truly need the extended transmit range for a legitimate, licensed purpose,

-

you accept the risk and warranty loss,

-

and whether the modification complies with the laws and regulations in your country.

If the answer to any of these is uncertain, the safest and most responsible choice is to leave the radio in its original, legally compliant configuration.

What Exactly Is the MARS Mod?

The term “MARS mod” originates from the Military Auxiliary Radio System (MARS) in the United States. MARS is a military support network that has existed since the 1950s, bridging civilian amateur operators with military communication needs. Alongside it is the Civil Air Patrol (CAP), which also uses radio equipment on frequencies close to the amateur bands.

Both organizations required radios that could transmit outside traditional ham allocations. Manufacturers responded by building hidden “switches” into their designs—jumpers, diodes, or firmware flags—that authorized service technicians to expand frequency coverage when necessary. Over time, hams discovered these hidden features, and the phrase “MARS mod” entered the community’s vocabulary to describe any unlocking of a radio’s transmit range.

Why Do Amateurs Perform This Modification?

The motivations vary widely.

-

Flexibility in emergencies – Some believe that in a disaster scenario, being able to transmit on a broader range of frequencies could help coordinate rescue efforts.

-

Operating abroad – Band allocations differ worldwide. A European ham visiting the U.S., or vice versa, may be tempted to expand their radio for compatibility.

-

Experimentation and curiosity – Amateur radio has always attracted tinkerers. Many simply want to understand how the manufacturers impose restrictions and how they can be lifted.

-

Participation in MARS or CAP – In the U.S., licensed operators in these programs legitimately require unlocked radios.

It is important to stress, however, that most of these motivations are not legally sufficient. Owning an unlocked radio does not grant permission to use it outside amateur bands.

How Manufacturers Implement Frequency Locks

Why can’t radios just transmit everywhere by default? The answer lies in regulation and liability. Manufacturers face strict certification standards (FCC in the U.S., CE in Europe, etc.) that require radios to stay within certain ranges.

To enforce this, companies use different methods:

-

Hardware jumpers or wires – early Alinco models could be unlocked simply by cutting or connecting a colored wire.

-

Keypad sequences – some Yaesu handhelds only required entering a hidden service menu.

-

PCB solder bridges – modern units like the FTX-1 rely on small solder pads that must be shorted or opened.

-

SMD diode matrices – advanced models (like the Icom IC-7300) use microscopic diode grids to configure regions, demanding expert soldering skills.

-

Software locks – increasingly, radios rely on firmware flags, accessible only through service software or hidden menus.

Each method balances ease of service with difficulty of tampering, but hams usually find a way.

Hardware vs. Software MARS Mods

-

Hardware mods are physical, often irreversible, and demand steady hands. They might involve cutting a trace, bridging a pad, or replacing components. Mistakes can be fatal for the device.

-

Software mods rely on service tools, programming cables, or firmware patches. These are less invasive but can still brick the radio if done incorrectly.

The Yaesu FTX-1 specifically uses a hardware jumper method, making it a classic example of a hands-on modification.

Examples of Popular Radios with MARS Mods

-

Yaesu FT-857 and FT-891 – both allow for solder pad modifications to expand frequency coverage.

-

Icom IC-7300 – relies on reconfiguring a diode matrix, a delicate operation.

-

Kenwood TS-2000 – capable of wideband operation with the right changes.

-

Baofeng UV-5R – infamous for its ability to transmit almost anywhere once programmed with free software like CHIRP.

Each case highlights a tension between user demand for flexibility and the manufacturer’s responsibility to limit misuse.

Legal and Ethical Considerations

A key truth must be repeated: performing the mod does not make it legal to use.

-

Internationally, the ITU defines band plans.

-

In the U.S., the FCC enforces strict rules.

Transmitting outside authorized bands can result in fines, equipment confiscation, or even license revocation. Beyond legality lies the ethical dimension: should hams knowingly risk interfering with emergency services? Should technical curiosity outweigh potential harm?

Most responsible operators agree that receiving outside ham bands is fine, but transmitting is another matter entirely. The spirit of amateur radio—“self-training, intercommunication, and technical investigations”—does not include unlawful operation.

Tips for Safe Modification

If you do proceed, follow best practices:

-

Read service manuals and cross-check instructions on trusted forums.

-

Back up settings or firmware when possible.

-

Use proper tools: fine-tip soldering stations, magnification, and antistatic precautions.

-

Never test by blindly transmitting. Use dummy loads, SWR meters, and power meters.

-

Always remember: a mistake on the air affects not just you but the entire spectrum.

Frequently Asked Questions

Do I really need the MARS mod?

Only if you are an official MARS or CAP operator, or if you have a genuine technical reason. For most hams, it is unnecessary.

Will I lose my warranty?

Yes. Any disassembly or soldering voids manufacturer support.

Can I transmit on emergency or police channels?

No. Unauthorized transmission is illegal and dangerous.

Can the modification be reversed?

Software mods often can, hardware mods rarely can. Some involve permanent changes to the PCB.

Can I receive outside amateur bands without modding?

Yes. Most modern radios already have wide receive coverage without modification.

Will it improve performance?

Not necessarily. The radio is optimized for ham bands; outside them, efficiency drops and stress on components rises.

Historical Background

Since the 1950s, MARS has played an important role in bridging civilian and military communication. During the Cold War, MARS operators provided contingency networks across the U.S. In natural disasters, they became lifelines when other systems failed. Manufacturers quietly enabled MARS compatibility to ensure readiness, but always under official authorization.

By the 2000s, as firmware programming became widespread, modifications spread beyond their intended audience. Online forums and YouTube tutorials accelerated this trend. Today, even newcomers with little soldering experience can attempt mods—though often with disastrous results.

Future Outlook

The future of transceivers is increasingly software-defined (SDR). With SDRs, frequency ranges are no longer determined by jumpers but by firmware. While this makes unlocking easier, it also allows manufacturers to implement stronger protections. We may see:

-

Encrypted or key-based access to expanded ranges.

-

Remote disable features to prevent misuse.

-

More distinct separation between amateur and commercial equipment.

At the same time, SDR opens new frontiers for experimentation. Amateurs can study spectrum use in ways never before possible, as long as they respect legal boundaries.

Expanding the frequency range of a transceiver through a MARS modification is undeniably intriguing. It combines hands-on technical skill, hardware knowledge, and that universal curiosity shared by radio enthusiasts who enjoy exploring what a device can really do beyond its factory presets. In a way, it even feels like a small act of defiance—lifting the limits imposed by manufacturers and uncovering hidden potential built into the radio’s circuitry.

But with that added freedom comes an equally important burden: responsibility. A modified Yaesu FTX-1 does not grant permission to transmit anywhere you wish, nor does it override national spectrum laws. The radio may gain the capability to transmit outside the amateur bands, but the operator retains the obligation to stay within the legal boundaries. Every expanded-coverage transceiver must be treated with caution, because a single transmission on a protected frequency—aviation, maritime, emergency services, military—can cause real-world interference.

For the vast majority of amateur operators, the true value of the MARS mod isn’t about unlocking forbidden frequencies. Instead, it is a chance to learn how modern radios are engineered, how firmware and hardware interact to enforce band limits, and how regulatory compliance is baked into the design. Exploring these aspects can deepen your understanding of RF systems, improve your troubleshooting skills, and broaden your knowledge of the spectrum as a whole.

And through all of this, one principle remains constant: the golden rule of amateur radio. Your skills, your experiments, and your curiosity should always contribute to the advancement of knowledge, the improvement of technical ability, and the support of the community. Amateur radio is built on innovation and exploration—but also on ethics, discipline, and respect for the spectrum. A modified radio is a tool, not a loophole. Use it thoughtfully, lawfully, and with an awareness of the responsibility that comes with expanded capability.

Image(s) used in this article are either AI-generated or sourced from royalty-free platforms like Pixabay or Pexels.