Is there still a role for longwave and mediumwave broadcasting in the digital age?

In recent decades, media consumption habits have undergone a radical transformation. The spread of internet usage, digital broadcasting (DAB, DVB), streaming services, and podcasts has significantly reduced the importance of traditional analog broadcasting. This is especially true for longwave (LF) and mediumwave (MW) transmitters, which played a defining role in national and international communication during the 20th century but are now often shut down due to their perceived technical and economic obsolescence.

But has their time truly passed? Or are there still arguments—in technical, historical, cultural, economic, or security contexts—that support maintaining terrestrial analog broadcasting, particularly on the longwave and mediumwave bands? This article explores the topic in depth.

The historical role of longwave and mediumwave broadcasting

In the first half of the 20th century, longwave and mediumwave radio were the primary mass communication tools globally. During wars, revolutions, and major political events, these frequencies ensured fast and wide-reaching public information dissemination. Stations like the BBC World Service, Radio Luxembourg, and Radio Free Europe reached millions of listeners through mediumwave.

From the 1930s onward, most countries built high-power mediumwave broadcasting networks, typically operating at 100 to 500 kilowatts. These transmitters could deliver signals over several hundred miles—especially at night, when atmospheric conditions favor MW propagation.

Longwave transmissions (150–285 kHz) achieved even greater distances and formed the backbone of national broadcasting in some regions, particularly where challenging terrain made other technologies impractical.

Technical characteristics and advantages

Longwave and mediumwave transmitters offer several technical benefits:

- Long-range coverage: Signals can travel hundreds or even over a thousand kilometers, especially at night.

- Wide area coverage: A single high-power transmitter can cover multiple regions or even an entire country.

- Simple receivers: No need for digital decoders or internet access—any basic AM radio can receive the broadcasts.

- Robustness: LF and MW frequencies are less prone to certain types of interference and can be received inside buildings or remote areas.

Drawbacks and challenges

However, there are also significant disadvantages that have contributed to their decline:

- Low audio quality: AM modulation is more susceptible to noise and provides lower fidelity than FM or digital formats.

- High energy consumption: A 500 kW transmitter can consume thousands of kilowatt-hours daily, generating substantial costs.

- Maintenance intensive: Transmitter towers, antennas, power systems, and cooling mechanisms require regular upkeep.

- Frequency congestion: MW bands are often crowded, especially at night, leading to interference.

- Perceived obsolescence: Most listeners now prefer FM, streaming, or digital radio.

Global trends – Europe, the Americas, and beyond

Europe

In the past two decades, many European countries have decommissioned their longwave and mediumwave transmitters. The BBC has shut down several regional MW stations, and France and Germany have completely ended their LF broadcasting. Numerous high-power MW stations have also gone silent.

Still, there are exceptions. Poland continues to operate its lone longwave transmitter (225 kHz), and MW broadcasts persist in countries like Romania, Hungary, and the Czech Republic, albeit in reduced numbers.

United States

The United States is a notable exception. AM radio (MW) remains an essential medium. Thousands of AM stations operate nationwide, broadcasting news, religious content, sports, and talk shows. In many small towns and rural areas, AM stations are the only real-time local information source.

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) has taken several steps to support AM radio:

- Promoting the HD Radio AM digital standard for improved audio and data capabilities.

- Supporting small AM stations through grants and policy changes.

- Allowing AM stations to use FM translators to reach audiences via FM frequencies.

Still, challenges remain:

- Car manufacturers like Ford and Tesla have removed AM tuners from some electric models due to electromagnetic interference.

- Younger generations rarely listen to traditional AM broadcasts.

Despite these issues, millions of Americans—especially older demographics—continue to rely on AM radio daily, making its disappearance in the short term unlikely.

Canada

In Canada, MW radio is slowly declining, but several regional and provincial stations remain active. CBC Radio One still broadcasts on MW in northern and underserved regions where FM or digital infrastructure is lacking.

Latin America

Countries like Brazil, Argentina, and Mexico still maintain extensive mediumwave networks. MW radio remains vital for rural and impoverished communities where internet access is limited or unavailable.

Australia

Mediumwave usage has declined in Australia, but a few AM transmitters remain active in remote areas for emergency broadcasting purposes. The ABC Radio network plays a key role in national disaster preparedness.

Asia and Africa

In countries such as India and China, mediumwave is still a major source of public information in rural regions. Across Africa, MW and LW remain crucial due to unreliable or absent internet and power infrastructure. The UN and various NGOs also use AM radio for humanitarian messaging.

Cultural and linguistic preservation

Many mediumwave stations broadcast in minority languages or dialects that are rarely found elsewhere. Analog AM radio has played a significant role in preserving local cultures and languages. In the digital age, these communities risk losing their broadcast platforms.

MW radio also supported cultural formats such as radio theater, spoken-word programs, and live storytelling—valuable traditions that have declined with the shift to visual media.

Emergency communications and national security

One of the strongest arguments for retaining longwave and mediumwave broadcasting is their role in emergency communications. In natural disasters, power outages, or cyberattacks, digital and internet-based systems may fail—leaving AM radio as the only viable communication tool.

Several countries—such as Switzerland and Finland—have retained at least one LF or MW transmitter as part of national emergency protocols. NATO also considers such infrastructure crucial for civil defense and resilience.

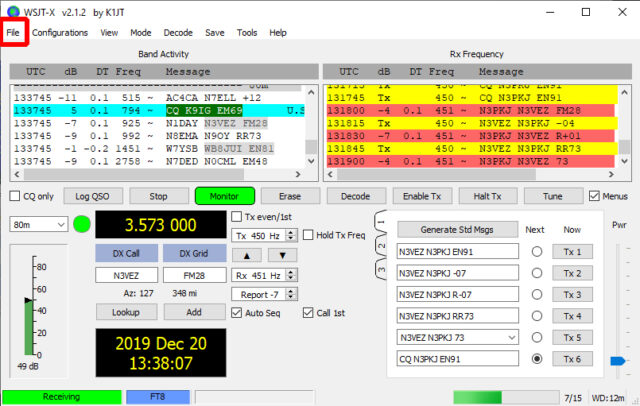

The role of radio amateurs and DX enthusiasts

Longwave and mediumwave bands are popular with amateur radio hobbyists and DXers—those who seek to receive distant radio signals. For these enthusiasts, monitoring, logging, and reporting MW and LW broadcasts offers both technical challenges and recreational value.

Many radio clubs and amateur organizations advocate for preserving or reviving existing MW/LW transmitters.

Future outlook

- Digital AM standards (DRM): Digital Radio Mondiale allows MF and LF transmitters to operate digitally, with enhanced audio quality and multiple services.

- Emergency backup networks: Existing transmitters could be downgraded for standby use during emergencies.

- Specialized broadcasting: Industrial, military, or scientific transmissions could justify continued use of these bands.

- Cultural heritage: Some transmitters—like Antenne Saar or Radio Romania Actualități—carry symbolic or historical value.

DRM and other standards like HD Radio offer technically and environmentally sustainable pathways to modernize AM broadcasting. However, widespread adoption will require global regulatory coordination, manufacturing support, and public policy commitment.

There’s also potential in reimagining MW for educational or community radio, including university stations that teach broadcasting fundamentals to the next generation.

Longwave and mediumwave broadcasting has undeniably declined as digital and internet platforms take over. Yet technical, cultural, hobbyist, and security arguments remain in favor of preserving these systems—perhaps not in their original form, but in repurposed, strategic roles.

With proper spectrum and infrastructure management, longwave and mediumwave are not obsolete—they are evolving. Policymakers should evaluate their future not only through economic lenses but within the broader context of global risks, communication resilience, and cultural continuity.

The future of radio may be digital, mobile, and interactive—but it also needs the lessons and resilience of the past.

Image(s) used in this article are either AI-generated or sourced from royalty-free platforms like Pixabay or Pexels.

This article may contain affiliate links. If you purchase through these links, we may earn a commission at no extra cost to you. This helps support our independent testing and content creation.