The hidden world of Part 15: inside the unlicensed micro-power radio experiments

Among radio amateurs and RF experimenters, one question has persisted for decades: is it possible to legally transmit radio signals without a license, purely for experimental purposes?

In the United States, the answer is yes — but only within very specific limits. These limits are defined by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) under the Code of Federal Regulations, Title 47, Part 15, which governs low-power unlicensed transmitters.

From this regulation grew an entire subculture of technical experimentation known as MedFER (Medium Frequency Experimental Radio), HiFER (High Frequency Experimental Radio), and BeFER (Between Frequency Experimental Radio).

Each of these systems operates with extremely low power levels and within defined frequency ranges, allowing radio hobbyists to legally explore signal propagation, antenna design, and receiver sensitivity — without ever holding an amateur license.

The significance of FCC 47 CFR Part 15

The FCC Part 15 regulations are among the most important in the U.S. radio landscape. They define how electronic devices can emit or intentionally generate electromagnetic radiation without needing individual licensing.

The idea behind Part 15 is to encourage innovation and experimentation, while ensuring that unlicensed devices do not interfere with licensed services such as broadcast radio, aviation, maritime communications, or satellite navigation.

Part 15 divides devices into two categories:

-

Unintentional radiators — devices that emit RF energy incidentally, such as computers or LED drivers.

-

Intentional radiators — devices that deliberately transmit RF, such as Wi-Fi routers, Bluetooth modules, or experimental transmitters.

Anyone operating under Part 15 must accept a key condition: no interference protection. If the device causes harmful interference, it must be immediately shut down upon request by the FCC or an affected licensee.

MedFER – Medium Frequency Experimental Radio

MedFER stands for Medium Frequency Experimental Radio, covering the frequency range between 530 and 1705 kHz, roughly the same as the AM broadcast band. Under Part 15.219, hobbyists are allowed to operate extremely low-power transmitters within this band.

Technical limitations (per FCC Part 15.219):

-

Maximum DC input power: 100 mW

-

Maximum total antenna length: 3 meters (10 feet), including feed line and ground wire

-

Frequency range: 510–1705 kHz

-

Typical modes: CW, QRSS, PSK31, or AM beacon operation

MedFER transmitters are generally not used for voice but for propagation beacons that send periodic identifiers or digital signals. Despite their low power, these beacons can often be received hundreds of kilometers away under favorable ionospheric or groundwave conditions — particularly at night.

Such stations provide valuable real-world data on MF propagation, antenna efficiency, and noise characteristics at low frequencies.

HiFER – High Frequency Experimental Radio

The HiFER band (High Frequency Experimental Radio) operates between 13.553 and 13.567 MHz, overlapping the globally recognized ISM (Industrial, Scientific, and Medical) allocation at 13.56 MHz.

Part 15 allows unlicensed devices to operate here if they comply with strict field-strength limits:

HiFER constraints:

-

Frequency: 13.553–13.567 MHz

-

Maximum field strength: 15 µV/m at 30 meters

-

Typical output power: often below 10 mW

-

Common modes: CW, QRSS, WSPR, PSK31

This 13.56 MHz ISM frequency is shared with RFID and NFC systems, but it’s also a sweet spot for low-power propagation experiments. Because the frequency is high enough for occasional ionospheric reflection, HiFER beacons can achieve global reception using SDR receivers and digital weak-signal modes.

The combination of worldwide ISM compatibility, simple hardware requirements, and measurable propagation makes HiFER experimentation a cornerstone of the “micro-power” radio movement.

BeFER – Between Frequency Experimental Radio

BeFER stands for Between Frequency Experimental Radio, and as its name suggests, it covers the 1.7–3.5 MHz range — between the MF and HF bands.

While there is no specific FCC subpart defining BeFER, experimenters operate under the same general Part 15 low-power limits.

BeFER transmitters typically operate around 1750–2000 kHz, using slow CW, QRSS, or digital beacon modes to explore near-field and nighttime ionospheric propagation.

Because this region lies near the 160-meter amateur band, it offers similar propagation characteristics but without the need for licensing, as long as emission limits are met.

The role of LowFER as the precursor

The LowFER (Low Frequency Experimental Radio) movement predated the MedFER and HiFER concepts. Operating in the 160–190 kHz range, LowFER transmitters under Part 15.217 may use up to 1 watt DC input and an antenna not exceeding 15 meters in total length.

Even at such low power, signals have been detected over 500 km away, especially at night.

LowFER systems became popular in the 1980s and inspired a generation of amateur scientists to experiment with low-frequency communication, ionospheric behavior, and groundwave propagation. Their success directly led to the expansion of unlicensed experimentation into higher frequencies — birthing MedFER and HiFER.

Decoding methods and SDR integration

Most MedFER and HiFER beacons use slow-speed digital or visual modes to remain detectable below the noise floor.

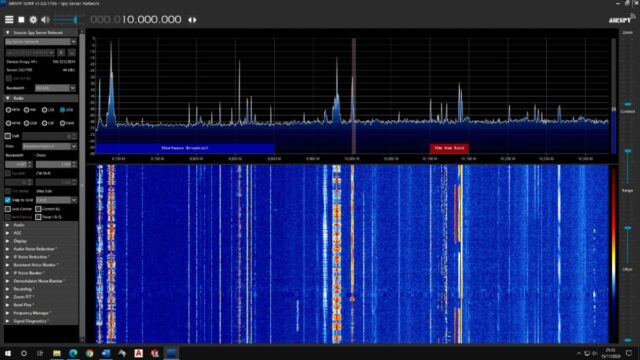

The QRSS mode, for example, uses Morse code transmitted at an extremely slow rate — each dot or dash may last several seconds. When displayed on a waterfall spectrum from an SDR, the call sign literally appears as a visual pattern, even when it’s inaudible.

Other beacons use WSPR, coherent PSK, or Hellschreiber to achieve similar detection through time-synchronized decoding.

Modern experimenters often rely on SDR receivers and software such as WSJT-X, FLDigi, Argo, or Spectran to visualize and log weak signals.

This integration of digital decoding and online SDR networks (such as KiwiSDR or WSPRnet) has transformed micro-power beaconing into a global, collaborative science project.

Global community and coordination

The unlicensed beaconing community maintains active coordination networks to prevent frequency overlap and document activity.

Sites like LWCA.net (LowFER/MedFER Coordination Association), HFUnderground.com, and WSPRnet.org publish beacon lists, propagation maps, and experimental reports.

These networks showcase hundreds of tiny transmitters from around the world — including the United States, Canada, Germany, Japan, and Australia — each operating legally within the confines of their national rules.

HiFER signals are regularly monitored by SDR stations worldwide, with their reception logged automatically online.

Some enthusiasts even use their beacons to monitor solar and geomagnetic effects on the ionosphere, turning hobbyist stations into small-scale scientific observatories.

Legal situation in Europe

Europe’s spectrum management is overseen by CEPT and ETSI, and while it allows certain license-free ISM bands, it does not permit general unlicensed radio transmissions for experimental communication outside those allocations.

The main license-free ISM frequencies under ERC/REC 70-03 include:

-

13.553–13.567 MHz (ISM)

-

26.957–27.283 MHz (RC devices)

-

433.050–434.790 MHz (industrial/data)

-

868.0–870.0 MHz (short-range devices)

-

2.4 GHz and 5.8 GHz (Wi-Fi, Bluetooth)

However, continuous beacon transmission on these frequencies is not allowed, even at microwatt power levels.

In Europe, anyone wishing to operate propagation beacons or experiment with continuous low-power transmission must hold an amateur radio license and comply with their national band plans.

For instance, in Hungary, such licensing is regulated by the NMHH, while in the UK it’s managed by Ofcom.

Nevertheless, the spirit of Part 15 experimentation survives through legitimate amateur beacon projects on the 10 m, 6 m, and microwave bands using WSPR, FT8, and other digital modes.

The philosophy of Part 15 experimentation

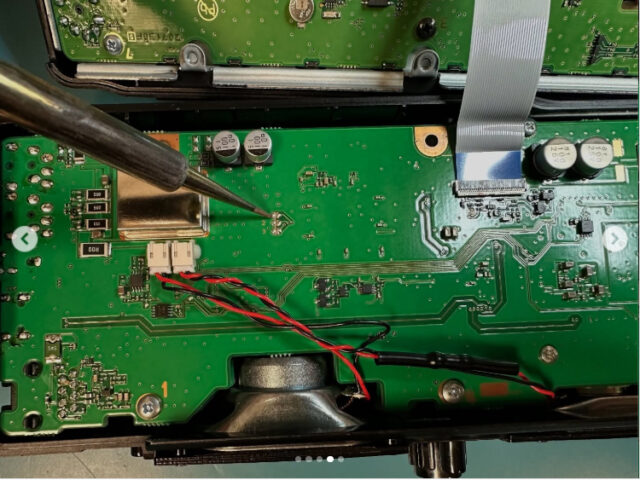

The beauty of Part 15 lies not in the power output, but in the precision and discipline it demands. Building a successful Part 15 transmitter means mastering oscillators, impedance matching, and noise suppression — every milliwatt counts.

It’s a philosophy rooted in curiosity and scientific integrity: prove what can be done with almost nothing.

Unlike typical high-power amateur operations, Part 15 experiments focus on efficiency, spectral purity, and measurement accuracy — qualities that align closely with professional RF engineering and EMC testing principles.

The future of micro-power radio

In the modern era, the relevance of micro-power radio has only grown. The technologies behind Part 15 — low energy, narrowband communication — are the same that power the Internet of Things (IoT), LoRaWAN, and low-power telemetry systems.

Many contemporary engineers designing RFID readers, NFC chips, or smart sensors are, knowingly or not, following the same experimental path that Part 15 pioneers began decades ago.

As energy efficiency becomes a central concern, these low-power communication methods represent the future of wireless connectivity — a direct continuation of the MedFER and HiFER legacy.

The FCC 47 CFR Part 15 framework remains one of the most influential pieces of telecommunications regulation in history. It has enabled generations of experimenters to explore radio physics legally and safely, leading to the enduring traditions of MedFER, HiFER, BeFER, and LowFER experimentation.

While Europe enforces stricter rules, the same scientific curiosity thrives under the amateur radio banner and ISM bands.

Part 15 represents more than just a regulation — it’s a mindset: that precision, creativity, and respect for the spectrum matter more than brute power.

From the quiet whispers of HiFER beacons to the digital heartbeat of global SDR networks, the micro-power philosophy continues to connect the world — not through volume, but through intelligence.

Image(s) used in this article are either AI-generated or sourced from royalty-free platforms like Pixabay or Pexels.