Kevin Warwick And The Birth Of The Modern Cyborg

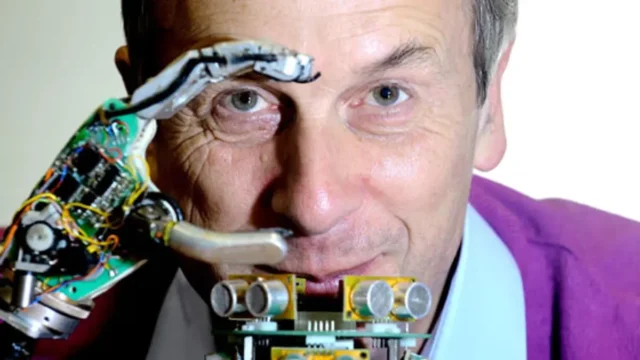

For decades, the word “cyborg” belonged almost exclusively to science fiction. It described half-human, half-machine beings with visible implants and superhuman abilities. In reality, the emergence of the cyborg was far quieter, rooted in laboratories and academic research rather than battlefields or movie sets. The most influential figure in this transition was Kevin Warwick, a British cybernetics professor who deliberately used his own body to explore the boundary between humans and machines.

Warwick was not the first human to receive an implant, but he was the first to consciously and publicly redefine himself as a cyborg. His work marked a turning point where human–machine integration stopped being a theoretical concept and became a lived, measurable reality.

What The Term Cyborg Means In Scientific Context

Outside popular culture, a cyborg is not defined by appearance. In scientific and cybernetic terms, a cyborg is a biological organism whose functions are extended or regulated by artificial systems through feedback and control mechanisms.

Three criteria are typically required:

-

a living biological body

-

an implanted or tightly integrated technological component

-

active interaction between biology and machine

By this definition, even a single implant can qualify if it participates in regulation or communication. Visible machinery or mechanical limbs are not required.

Kevin Warwick’s Academic Background And Motivation

Kevin Warwick was a professor of cybernetics at the University of Reading in the United Kingdom, working in robotics, artificial intelligence, control systems, and human–machine interaction. His research interest was not limited to building smarter robots. Instead, he focused on a deeper question:

what happens when the human nervous system becomes part of a digital control system?

Rather than treating humans as external operators of machines, Warwick wanted to explore humans as integrated components within technological systems. To answer that question properly, he chose self-experimentation.

Project Cyborg 1.0 And The First Conscious Human–Machine Integration

In 1998, Warwick launched the first phase of his research, later known as Project Cyborg 1.0. A small RFID transponder was surgically implanted into his forearm. From a hardware perspective, the implant was simple. From a conceptual perspective, it was revolutionary.

The implant allowed Warwick to be automatically identified by computer systems in his workplace. As he moved through the building:

-

doors opened automatically

-

lights activated

-

computers logged him in

-

phone systems redirected calls

No cards, keys, or passwords were involved. His body itself became the interface.

Why Project Cyborg 1.0 Was Historically Important

The significance of this experiment was not convenience, but identity integration. Warwick was no longer a user interacting with machines. His biological presence directly triggered digital actions.

This experiment anticipated many modern technologies:

-

biometric authentication

-

passwordless access control

-

implantable RFID and NFC systems

-

ambient and context-aware computing

Project Cyborg 1.0 demonstrated that human identity could be embedded into infrastructure at a fundamental level.

Project Cyborg 2.0 And Direct Neural Integration

The second phase of Warwick’s work represented a far more radical step. In 2002, a microelectrode array was surgically implanted into his median nerve. This implant was capable of two-way communication between his nervous system and a computer.

Unlike the RFID chip, this was an active neural interface. It could:

-

read electrical signals generated by nerve activity

-

decode movement-related impulses

-

send electrical stimulation back into the nerve

This created a closed feedback loop between biology and machine, fulfilling the strict cybernetic definition of a cyborg.

What The Neural Implant Was Able To Do

The neural interface allowed Warwick to control external systems using nerve signals alone. More importantly, it allowed artificial signals to be injected back into his nervous system, producing sensations generated entirely by technology.

This meant:

-

movement could be translated into data

-

data could be translated back into perception

-

the nervous system could be extended beyond the physical body

At this point, Warwick’s nervous system was no longer isolated. It had become part of a hybrid control network.

The First Human To Human Neural Communication

One of the most remarkable aspects of Project Cyborg 2.0 involved Warwick’s wife, who received a simpler neural interface. Neural signals from Warwick were transmitted over a network and delivered as stimulation to another human nervous system.

This was not mind reading or thought transfer. The signals were basic neural impulses. Even so, this was the first documented case of direct electronic communication between two human nervous systems.

The implications were profound:

-

nervous systems could be networked

-

sensory input could be technologically mediated

-

human experience could be partially detached from physical reality

Why Kevin Warwick’s Work Was Different From Medical Implants

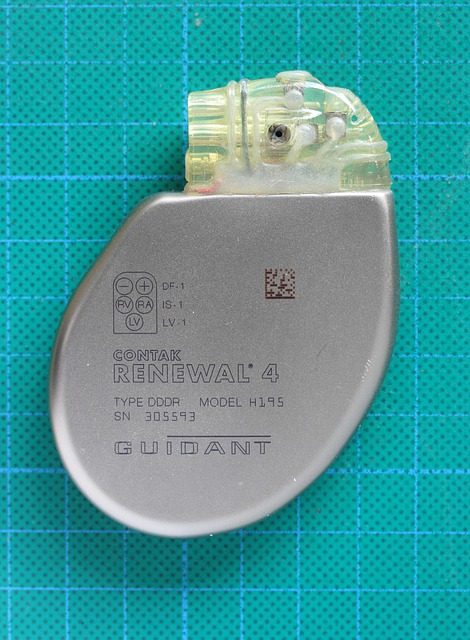

Implantable medical devices existed long before Warwick. Pacemakers, cochlear implants, and deep brain stimulators all rely on electronic interaction with the body. The difference lies in intent.

Medical implants are designed to restore lost function or treat disease. Warwick’s implants were not therapeutic. They did not fix a medical problem. They explored new capabilities and new forms of integration.

This distinction places Warwick’s work firmly in the domain of human augmentation, not medicine.

Cyborg Identity, Autonomy, And Control

Warwick’s experiments raised critical ethical and philosophical questions that remain unresolved:

-

who controls an implant once it becomes part of the body?

-

who owns neural data?

-

can implanted systems be modified, disabled, or exploited?

By allowing machines to interface directly with his nervous system, Warwick demonstrated that the human body could become a programmable environment.

Kevin Warwick Versus Modern Biohacking

Warwick is often associated with biohackers, but the comparison is inaccurate. Biohacking typically involves informal self-experimentation with limited oversight. Warwick’s research was conducted in academic laboratories, with ethical review, peer-reviewed publications, and transparent documentation.

His work was not performance art. It was structured, data-driven science.

Long Term Impact On Technology And Research

Many modern technologies trace their conceptual foundations to Warwick’s experiments:

-

brain–computer interfaces

-

neurally controlled prosthetics

-

rehabilitation robotics

-

neural signal decoding for artificial intelligence

While today’s systems are smaller and safer, the core principle remains unchanged: direct interaction with the human nervous system.

From Human Ownership To Human Integration

Perhaps the most lasting legacy of Kevin Warwick’s work is philosophical. His experiments challenged the idea that technology is something humans merely use. When technology is implanted, it cannot simply be turned off or discarded. The human body becomes both user and platform.

Kevin Warwick was not the first implanted human, but he was the first to deliberately cross the boundary into cyborg identity. By embedding machines into his body and nervous system without medical necessity, he demonstrated that the cyborg is not a science fiction concept but a technological reality. His work reframed human–machine integration as a matter of choice, ethics, and control. The question left unanswered is no longer whether humans can become cyborgs, but how society chooses to define the limits of that integration.

Image(s) used in this article are either AI-generated or sourced from royalty-free platforms like Pixabay or Pexels.